Less is More

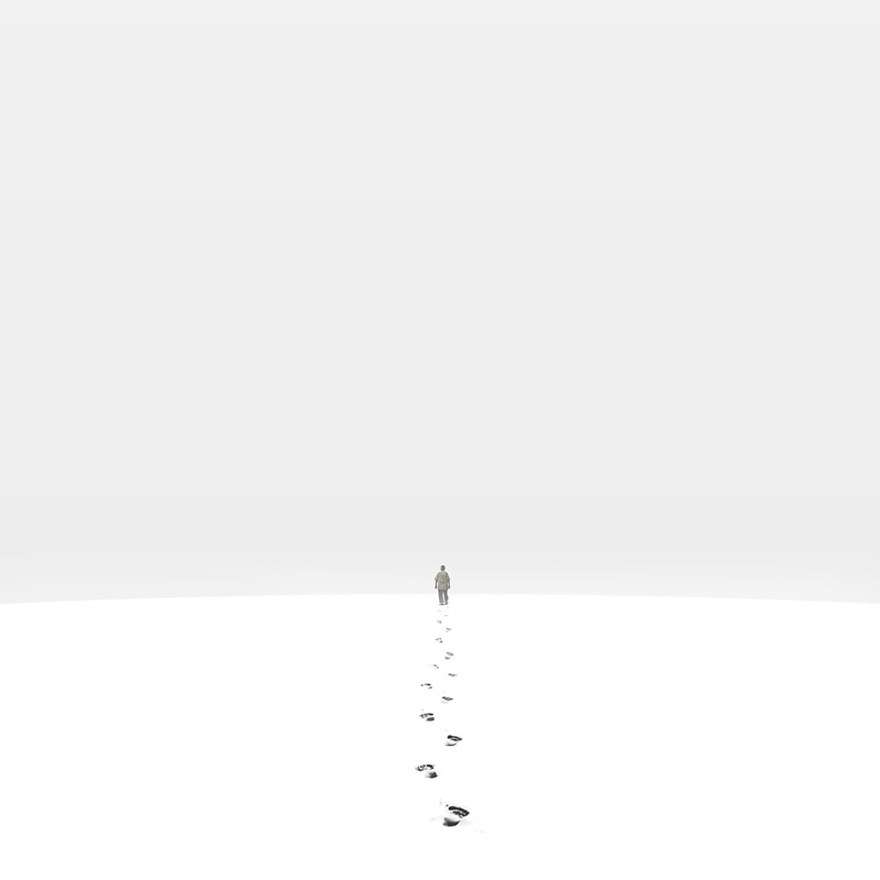

“Less is More” is both the mantra of minimalists and authors. I believe there is truth in the statement from both perspectives but I believe this message of minimalism can be more accurately applied to writing by adding the also-common-minimalist-mantra “that I love.” That’s not quite enough either but Hemmingway’s prose was too reactionary to discover the beautiful message of minimalism. Let me explain – my journey is not unlike others but it’s the details that deliver the powerful message here.

I’ve been moving along a personal minimalist journey for a few years now. Dejunking, decluttering, and “letting go” has been a long, painful process, mostly because sometimes, as a husband/father, I sometimes fail to inspire my family with the same vision I have. Leading by example requires not only vision but fulfillment and accomplishment so when a vision is family-wide, it’s easy to get caught up in the web of instilling vision where only vision exists and example gets lost in a very large family. So, we learned together.

My Minimalist Journey

Originally, I started a family tradition of giving away something every time we received a gift because I felt like we were accumulating too much stuff. After-Christmas-tradition was to give away toys the children no longer loved to less privileged children. That went well but created more status-quo than real change. It did instill a desire in me to dejunk more so we tried that too. Our first philosophical question was the perfect example of Soren Kierkegaard’s radical subjectivity (viz, everyone applied it differently): “Is this excess? Do I really need this or is it junk?” We made progress though – especially when the question was modified to “When was the last time I used this or even thought about it?” (computers tell us this is the best method, btw) Our garbage can was overflowing for a few weeks or more and trips to donate items to thrift stores increased. Eventually though, our family needed a new philosophy to make better progress.

My wife discovered the Kon Mari method. This required a new evaluation: “Does this item bring joy?” If it does, you keep it – AND – you take better care of it by learning principles of stewardship unique to the Kon Mari method. If it doesn’t bring joy, you “let it go,” which is maybe something less drastic than just “getting rid of it.” That method created substantial changes in my family and we made good progress. However, my too-clever-for-her-own-good daughter determined that she loved everything she owned and it all brought her joy so she didn’t get rid of much. She was our hoarder and the secret to a family mystery: long lost items were discovered where she kept her other secret treasures (under her bed). We needed something more – and not just for her. As a family, we still had way too much stuff.

It took a few more philosophies to bring me to the beautiful understanding of minimalism that Kon Mari probably understood from the beginning but we’d failed to grasp. Here are a few methodologies (and I promise this has everything to do with Hemmingway and writing):

- Do I want to clean this thing?

- Is taking care of this more painful than the joy it brings?

- Could someone else find greater joy in having this thing?

- Are you keeping it out of guilt?

- Are you more excited about this item or another one similar to it?

The answer to the first question is usually “no” and inspires a lot of dejunking! However, if I ask that question about my saber tooth tiger skull, I have to say, I don’t mind taking care of it. It’s cool, inspiring, and requires little upkeep and it generates a lot of fun conversations when people visit. The second question is similar but is helpful because sometimes, you don’t mind taking care of something at first but eventually, it grows into a burden. When that happens, it’s time to get rid of it (this happens in writing, too). Would someone else enjoy the item more than you? Look for that win/win. Keeping it out of guilt? Family heirlooms can be like this, as can be items we keep simply because it belonged to someone else (perhaps, like some fantasy tropes; I won’t mention my bias against goblins, dwarves, and gnomes here but I’m tempted …). The last question can be very difficult. You CAN have more than two items that do the same thing in minimalism if there is a purpose to do so (some families keep day-to-day dishes and special occasion dishes, for example). However, sometimes this question really seals the deal.

After trudging through these questions/philosophies with my personal things, I’ve nearly arrived where I want to be. As a family, we’re still growing but we’re doing better and I can finally lead by example. Here is the final lesson that I learned from that experience that applies not only to authors but many other professions and areas of life.

My Minimalist Arrival … Buried in a Stack of Papers

I had a collection of papers that comprised (at least) approximately eight linear feet of research (stacked) for some non-fiction books I’m interested in writing. Looking at each piece of paper (usually articles), I could genuinely say that I was very interested in reading the article again or, sometimes, for the first time. Kon Mari method: did I love it? Yes! I wish I could be a professional student, a full time researcher! Was taking care of the stack of papers more painful than the joy it was bringing? That was hard to say because they were heavy and I rarely found the time to get back into those articles I wanted to read … but I still wanted to. I wasn’t keeping them out of guilt and it is unlikely that anyone else would enjoy my personal collection. Was I more excited about similar items? That was tricky. I’m not even certain what that might mean.

Before I sorted the paperwork, I thought I was just as excited about each of the articles as any others. After I sorted them, I changed my mind. To get there, I had to make a decision: somehow, I wanted to get rid of most of those papers, maybe 90% or more – but how? None of the above methods were really working for me but what I’d been learning from my minimialist-journey was that taking care of things is a burden. You can’t fully realize this until you allow yourself to walk the path of minimalism and trust in the experience of other people. The less things you have, the more time you have to devote to whatever really brings you joy and the easier it is to enjoy whatever you do keep. There’s an intangible feeling of joy when you get rid of enough “stuff” to allow yourself to fully enjoy what you have. So, sorting through papers, I just asked myself: “Is this research I can’t live without?” Not literally. Papers aren’t food. But was I so excited about an article or research notes that I’d undoubtedly regret parting with them until I at least read them (if not take the time to underline, note-take, and incorporate into some book)? Only after that approach was I able to let go of all but one linear foot of research – and it was fun!

That’s what brought about a huge realization. As I sorted through that last foot of material, I grew elated. I couldn’t think about anything else in my free time besides how I wanted to compare the findings of one article with the fact lists I’d seen in another article, and how I could get rid of some of the remaining physical articles if I simply moved my notes from the papers onto a digital platform where I’d actually use them for a project. Soon, I was down another half-inch of materials and looking at massive progress on a book that I’ve felt passionately about for years but never got around to beginning. I’d been stuck in the research mode but now that I knew where everything was and put together, I could finally pluck some of the fruit I’d been growing.

Minimalism Beyond Hemmingway

What does this have to do with Hemmingway and several other disciplines of western culture?

In my opinion, Hemmingway was understandably, but overly reactionary, pushing against centuries of flowery, tediously loquacious writing styles that droned on and on about landscapes, cityscapes, and other details that often derailed the pacing of a story. Hemmingway loved plot and swearing, not prose. And a generation of people tired of purple prose and stories that barely trudged along embraced his pared-down-to-the-bones style of writing. I enjoy some of his books but frankly, his prose is often ugly, jarring, and unnecessarily base. He pared things down so much that the leftover prose was often ugly – too far left from the too far right of his peers.

Authors, as lovers of words, often fall into the enticing trap of nineteenth century purple prose and so editors often tell us to keep trimming things down so we don’t bore our “average” audiences. Fast paced thrillers often benefit from this treatment – as do action movies – but this isn’t too surprising. Thrillers are all about the plot and suspense. They are not intended to be relaxing journeys. They’re a race through a tight plot line, not a meandering journey through the comforting forests of inspiration. They’re certainly not conducive to Tom Bombadil excursions.

That doesn’t mean that we have to remove beauty from our prose, though. Great movies are more fulfilling with beautiful cinematography; elegant prose can enhance emotional passages if crafted well. Almost anywhere, there is room for beauty, even for the sole purpose of making your villain appear all-the-more sinister. Much of our generation has lost site of this. Worse, we’ve gone to an extreme where even best sellers lose clarity by trimming away too much.

Minimalists sometimes forget this principle as well but in minimalism, you’re supposed to thoroughly enjoy everything left in your home, in part, because it allows you to time to enjoy things that are truly meaningful – so they find beauty either in their lifestyle or in their environment or both. Applied to writing, prose can be both eloquent and succinct – if we’re not too caught up in the corporate spit-out-as-much-as-possible to maximize profits mode. I applied these principles when outlining Sea Dragon Apocalypse. I had far too many exciting ideas to put in one story – even the core story I’m trying to tell. Because I took the time to carefully outline the novel, I was able to pare down all of those cool details that were more distraction than substantive and leave nothing besides plot points that advance the story as fast as possible. Then, as I’m writing, I’m able to dedicate more energies to creating evocative and beautiful prose instead of editing out passages that ultimately weren’t worth including in the novel. (You can check out my progress on the toolbar to the left, by the way).

In summary, it’s possible to find the proper balance of applying minimalism to plot lines so the story advances quickly while still investing time in crafting passages that are akin to beautiful cinematography: they can create an unobtrusive sense of awe that plunges your reader farther into the plot because vivid descriptions awakened the reader’s imagination more thoroughly than a skeletal passage or description. That’s not to say that prose itself shouldn’t be pared down. It often should be pared down. However, there is a balance to strike here, a balance that Hemmingway awakened us to but failed to perceive in full. Genius is often like that: it sees what no one else sees while leaving room for a new generation to improve upon.

Your minimalism is inspiring to me <3.

Danke – I’m just a spring chicken in some ways but … trying hard!

Along the same lines as what you were expressing on minimalism and how much stuff you should have… I think all the extras are nice …only if you have the capacity to maintain it and/ or desire to spend the time to care for it more than your desire the time to do “other things”. If it belongs to you, but you are not motivated to “shine” it regularly, just get rid of it. Maybe you think you are motivated but it gives you an overwhelmed feeling to think about giving it energy to care for it, this is a good sign too that it is not blessing your life to have it.

Along the same lines that you were expressing concerning minimalism and how much stuff you should keep…. I have really found it true that if you are not motivated to “shine” it then it is a good sign that you should not keep it. If it brings you pleasure to care for it, then keep it, but if you feel overwhelmed even just thinking about barely maintaining it, get rid of it. Maybe it is not as bad as feeling overwhelmed but you are more interested in other things more than you are in caring for your item. It easy for these items that don’t overwhelm us but just are not capturing an excited interest any more to heavily accumulate in our lives. They don’t stand out as a thorn but their effect can be more like a feeling of lack of Oxygen giving us a burnt out feeling and we don’t even now why. Freeing ourselves from these things can be like a breath of fresh air, invigorating and freeing our mental energy for more exciting things in life. I know that it is a keeper for sure if not only am I happy to maintain it but it brings me pleasure to go the extra mile to care for it. It begs the question, maybe if I don’t feel that way then is it time to free myself from it? I have found sometime I feel like other things are keeping me from caring for the thing I want more, I feel overwhelmed because I feel kept from caring for it. You really can only have so much stuff before you feel that way. Everyone has different capacity levels. Most of us are over our capacity levels. It can feel like an accomplishment just to get it down to match our capacity levels, but that also begs the question: do you want to sit on your maximum level? Is that the energy level you want to keep? Most of us would say “no”This is why maybe almost too little can be so freeing. You will have burst of creativity to create things yourself to enhance your environment making what you have more fulfilling any way and give the sense of a stream ever moving and joyful instead of stagnant and stuck. Letting go creates a flow.

I totally agree – even if something makes you happy, there is a point where the pain of upkeep overwhelms the joy it brings. It’s a tricky balance but it seems that less is more and that this is a difficult concept for people who grow up in industrialized societies to fully realize because we are inundated with things and a culture of acquiring things.

Sorry about two very similar posts 🤦🏼♀️. I tried to post the first one and the computer said it was unsuccessful in posting it. “Great” I thought “now I have to try to rewrite it”… …only to later see that now I have two and they both say similar things. Technology sometimes 🙄. Sorry about that!